Recently I went on a private reunion with some old school friends; we took a house by the sea for the weekend, about three hours north of San Francisco. There was both interest and charm in seeing how time had dealt with my friends; on the verge of middle age they had become, one could not help noting, women of certainty and dominance, respected and confident in their fields and at ease (from the outside, at least) with their family ties. (“They told me I was intimidating,” said one soft-spoken, iron-willed MD; “do you think I’m intimidating?” Well, honestly, I did, a bit; but in the nicest possible way.)

The friend who had arranged the house brought vegetarian food, and explained, as she captured an insect and released it into the outdoors, that she had become a practicing Buddhist. As such, she eschewed distractions from the path, right down to spices in her food. (No sex and no alcohol went without saying.) I, on the other hand, had become more sensual and earthbound with the years. As a young student, I had been half out of my body at all times; no one more Descartian, more fixed in the mind, from which I dwelled in a kind of mooring-roped balloon a short distance above my physical self.

But you know, one gets used to things with time. My body, my writing, the dangers of a career with no fixed milestones. I was becoming more at ease and more experimental; playing with erotic fiction, making new friends, wandering the Net, moving across the country to enter a new field. The beauty of growing older is that after one has made a fool of oneself enough times, the idea no longer holds quite the same terror.

And you know, I think I’m not alone in this. Many women grow into their bodies and their self-confidence; we’re no longer unwilling to go to battle when it’s necessary, while men perhaps feel less required to fight. An outspoken New York lawyer I know expressed her growing sensuality characteristically: “I’m telling you, Doris, it’s being in your late thirties. It’s like your body is saying, ‘I’ve only got three eggs left, and by god they’re gonna count.'”

Even at this reunion, spartanism was hardly the order of the day. My Buddhist friend inquired one evening how we wanted to spend the time after supper. Was there any question? I wondered. I said, “I thought we’d take the champagne and chocolate out to the hot tub, chat till we’re prunes, then come in and dry before the fire.” Another friend put her hand on mine and said earnestly, “Doris, you are a woman after my own heart.”

Where did this willingness to take delight come from? When I was in college, I would sometimes stay up all night finishing a paper or studying for a test, then go up to the roof to watch the sunrise. From this distance, a continent and a lifetime later, I can see that the paper and the test have faded, but the sunrise remains. For me, the sunrise was and is a lesson I need to learn, perhaps the way my friend needs to learn Buddhism. My own heart lies with Yuan Mei, a Chinese poet who wrote adventure stories and took lovers and created the standard text on a certain poetic form — and who once ran out of a Buddhist temple because he saw a poem on the wall that he loved, and he had to go and find the author then and there. (He did find him, and they became friends for life. What more can one ask?)

My lesson is to appreciate the toys the universe has in its attic — the hot tub, the chocolate, the sunrise — without taking them so seriously that I would pine in their absence. Exploration, not avoidance, has become the order of the day. And it’s an order whose carrying out has uncovered with every year a new thing to enchant. Four years ago I would never have believed I could take the slightest interest in, say, the campaigns of Napoleon. Now friends send me his soldiers’ memoirs as Christmas gifts because they know I’ve become fascinated with the time and place and attitudes. With every year I become aware of new standards of beauty and personal style; men and women I would not have properly appreciated once now seem attractive. What would happen, I sometimes wonder, if the human lifespan increased dramatically? Would our tolerance and aesthetics increase with it? Would all knowledge eventually take our fancy, all people and animals make their beauty clear?

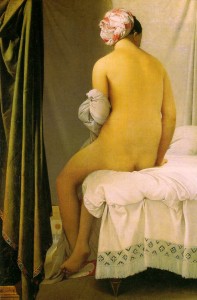

I had always had a liking for the carefully drawn sketch or Dutch interior, but about four years ago I found myself buying a huge, glassed print of Ingres’s “Odalisque.” The detail work of the silk and the peacock feather were irresistible, but really, here was this enormous, nude woman, her skin translucent as mother-of-pearl, reclining on a luxurious bed — what the heck was I going to do with this? Put it on my mantle?

I did. It took over the room. But what the hell, I was in a classical mood anyway, and followed it up with a painted, Empire-style pillar between the two front windows. In an old New York railroad flat, with Victorian molding on the walls, one can get away with drama like that. Still, guests sometimes looked to the enormous painting and then looked back at me, as though wondering if they should ask what in god’s name had entered my head — the finely drawn interior of a Paris walk-up that lay atop my bookcase seemed much more my style, and accessible to contemporary taste.

And it was only the beginning, I’m sorry to say. I came across a set of cards from the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art; “Ingres Details,” they were called. Rich swatches of patterned fabric, the curve of a plump, glowing hand, a dark and knowing eye. It was remarkable; the man’s love of these things communicated itself to the viewer in a telepathic spill, just as a writer’s love of her character will magically transmit itself to the susceptible reader. It was as close as to a tactile use of paint as one could come without trompe l’oeil; and the kicker came a mere two days later, when I watched the next episode of Sister Wendy’s History of Painting, and this pleasant and near-elderly nun in full habit confessed to a “soft spot” for Ingres. She displayed a picture of a naked woman — I realize that, with Ingres, this is not specific enough — shown sitting on a bed, from behind; and she discussed Ingres’s apparent sensual enslavement to the curve of a woman’s back. It was not, however, till she described the paint as looking “as though it had been licked on,” that I realized our nun was in no danger of becoming a Buddhist. (“My dear Sister Wendy,” came the unbidden thought, “you are a raging sensualist.”)

Beware them, women of a certain age. You have been warned. (Unless you are yourself a woman in your twenties. In which case, you have been promised.)

Originally posted September 29, 1997.